The Culture of Poverty

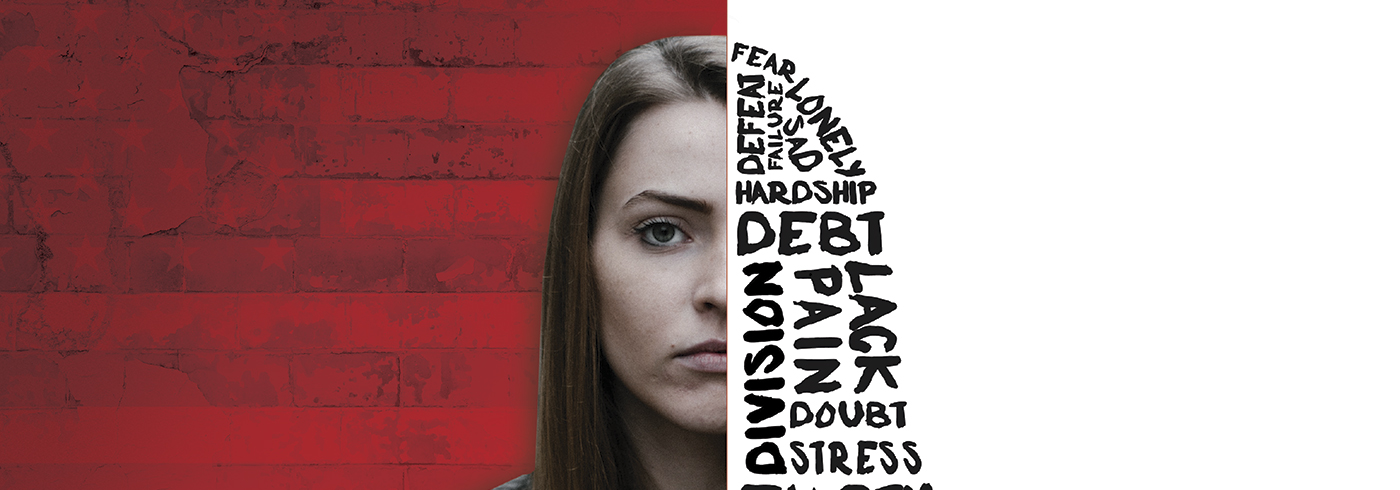

Understanding the hidden divide in your church

We led a growing church in the urban sprawl of Dallas. Our community was diverse, and by the favor of God, our church reflected that diversity. We developed an outreach that grew to thousands of people and became the signature of the church and the focus of our heart for the city. Our efforts in the community led not only to ethnic diversity but also socioeconomic diversity, which brought both blessings and challenges.

We’ll never forget the series we did at Christmas one year where we brought a family struggling to make ends meet on stage to blow their minds “Extreme Makeover: Home Edition” style. We pulled the curtain back to reveal a new washer and dryer, furniture and Christmas gifts for all the kids. The congregation applauded, and we felt good that we were faithfully helping the neediest among us.

What struck us in that moment was the father’s expression during our big reveal. He was stone-faced. The mom and the kids were ecstatic and in tears, but not the dad. We couldn’t understand why he wasn’t as overwhelmed by our grand gesture as everyone else. It wasn’t until later that we understood we had unintentionally reminded this man of his inability to provide these things for his family, and we put his insecurity on display for all to see.

Just as ethnic diversity requires cultural awareness, so does socioeconomic diversity. Our church enjoyed tremendous growth because of our outreach efforts in the community over the years. The more we grew, however, the more we realized we had a growing divide in our church. There was a culture of poverty we didn’t understand, and it was having a negative, albeit subtle, impact on our church.

Our well-meaning efforts to minister to the poor created awkward moments and forced us to reconsider how we ministered. The fact is, it’s easier to minister to people from all walks of life than to integrate them into the life of the church and create real spiritual community. Yet a unified Body that grows together and lovingly bears one another’s burdens is what God calls us to become.

The Nature of Poverty

The statistics on poverty in the U.S. are concerning. In 2015, 43.1 million people (13.5%) were in poverty. Nearly 24.5 million people (12.4%) ages 18 to 64, 14.5 million children (19.7%) under 18, and 4.2 million seniors (8.8%) 65 and older were in poverty. In 2015, the Census Bureau defined the poverty threshold as less than $25,000 for a family of four. Families fitting that description are in virtually every church and community in America.

Per the American Psychological Association, poverty has profound implications on the nation’s housing, education, health and economy. Substandard housing, homelessness, poor nutrition and food insecurity, inadequate child care, lack of access to health care, unsafe neighborhoods, and under-resourced schools adversely impact families in poverty.

Poorer children and teens are at greater risk for poor academic achievement, school dropout, abuse and neglect, behavioral and emotional problems, physical health problems, and developmental delays. The barriers that children and their families encounter when trying to access physical and mental health care compound these effects.

Economist Harry J. Holzer estimates that child poverty costs the U.S. economy an estimated $500 billion a year, reduces productivity and economic output by 1.3 percent of GDP, raises crime, and increases health expenditures.

The absence of a father increases the likelihood of poverty. Among fatherless homes, the poverty rate is 47.6 percent.

With such far-reaching effects, the church must have a response to poverty, not only addressing its symptoms, but also its causes. A better understanding of the culture of poverty will assist the church in this effort.

In her book, A Framework for Understanding Poverty, Ruby K. Payne defines poverty as “the extent to which an individual does without resources ... the resources that influence achievement: Financial, emotional, mental, spiritual, physical, support systems, role models, and knowledge of hidden rules.”

Payne identifies 15 subcultures and illustrates how economic classes ascribe different rules to each subculture. For example, she says that within the subculture of time, the poor place value on the present, the middle class on the future, and the wealthy on traditions and history. Within language, the poor favor casual speech and view language as a survival tool, while the middle class use formal speech and see language as a negotiation tool. The wealthy speak formally and view language as a networking tool.

According to Payne, “The hidden rules of the middle class govern schools and work; students from generational poverty come with a completely different set of hidden rules and do not know middle class hidden rules.”

A lack of awareness of these rules can be one more obstacle for the poor in trying to obtain jobs that will lift them out of poverty. Payne says eight areas of resources — financial, emotional, mental, spiritual, physical, support systems, relationships and role models, and knowledge of unspoken rules — need attention for students to reach their potential at school. Church ministries could also benefit from such a holistic approach. Simply equipping the poor with more financial resources isn’t enough.

How Poverty Affects the Church

The Church has always wrestled with how best to minister to the poor. Addressing poverty is expensive, time-consuming, and, often, a moving target.

Churches are limited in their financial resources. In the church that we led, we always had more requests for help with rent, utilities, food, and health care expenses than we had money to give. Every time we had to say “no,” it took a toll on us.

As we began to develop ministries that would truly address the causes of poverty and not just the symptoms, it eased our minds, but those ministries are difficult as well. Just as work schedules and transportation issues affect schools, we saw inconsistent attendance in parenting and financial classes at our church. The desire was there, but the logistics were tricky.

Those living below the poverty line deal with such issues as inconsistent work schedules, transportation and availability. We realized it wasn’t enough to provide the class and materials; we needed to help families overcome these obstacles. Money isn’t the only answer, because money isn’t the only problem. Poverty has a cruel way of affecting people’s lives far beyond their pocketbooks.

A correlation exists between poverty and the single-parent family, which presents both opportunities and challenges for the church. We saw the toll on children’s ministry volunteers as more families in poverty began to attend our church. Frankly, the children were more disruptive. This was not due to their financial standing, but, more commonly, to the absence of a father.

Of course, cultural ideas about acceptable church behavior contributed to the problem. We often imposed our middle-class values on all the children in our church. We realized we needed to train leaders and volunteers to work with children who were coming with a different set of values and who had faced unimaginable problems. We needed to educate our church about the economic biases we all had and lead the way in becoming unified.

Any time multiple cultures coexist, tensions and complications can arise. As pastors, we found it more difficult for people to cross economic lines than racial ones. Churches today frequently discuss bringing together people of different generations and races. Are we as intentional about economic diversity in every aspect of ministry? Are there only opportunities for the wealthy to minister to the poor, or are the poor ministering to the wealthy as well?

A unified Body that grows together and lovingly bears one another’s burdens is what God calls us to become.

After all, a lack of financial resources may allow for a surplus of spiritual resources. (We certainly see examples of this in Scripture.) If so, the poor in our church could have as much to offer the wealthy as the wealthy believe they have to offer the poor.

Beyond Outreach to Understanding

Understanding the values and challenges of different economic realities is vital for all leaders and volunteers in a church. In healthy churches, people aren’t just sitting next to one another; they are discipling one another, developing relationships with one another, and serving one another. To start cultivating such a culture of unity, the pastor can consider three key questions.

1. What is the economic reality in my community? Consider what led to the poverty in the community. Is it generational or circumstantial? What have community leaders identified as the main contributing factors to the community’s poverty, and what do they need the church to do to address the causes, not just the symptoms? Study the middle and wealthy classes to learn what career fields are predominately represented. How is the city geographically divided between economic lines? What area is your church located in?

2. What values are represented within each class? Each culture values different things and demonstrates those values in different ways. The leader’s job is to understand each set of cultural values and help people recognize the values they have in common.

3. How are we teaching the people in our church to let go of economic biases? This is a difficult conversation to have. But with prayerful, intentional community building, the church may become the nation’s most unified institution.

The Power of Relationship

Payne says, “Individuals who made it out of poverty usually cite an individual who made a significant difference for them.” In other words, relationship is the most important factor in breaking the cycle of poverty.

As the Church, we believe the most important relationship is a relationship with Jesus. Sharing and living the power of the gospel is the most vital strategy we can employ in helping people find freedom from the strongholds that bind them. We see a beautiful picture of the New Testament Church in Acts 2:42-47.

The Holy Spirit levels the playing field and helps create true spiritual community and authentic ministry. As the story of the Early Church unfolds in Acts, we see that the members certainly weren’t without their social and ethnic issues (Acts 6,11,15). Yet, the Holy Spirit led them not only to deal with those issues, but also to meet the needs of the people around them, while at the same time grafting people from all walks of life into the body of Christ.

We, too, need the leading of the Holy Spirit to deal with the issues we face today. We need spiritual mothers and fathers who nurture spiritual sons and daughters like Paul did for young Timothy and, even more poignantly, for the slave Onesimus.

People don’t need to learn middle-class values; they need to learn biblical values — values embodied in the person of Jesus Christ. They need to know Him. Whether they ever escape a financial poverty, they will be wealthy in spirit, which is the greatest Kingdom value. We do know that obedience to God and serving Jesus lead to blessing. We don’t always know what form those blessings will take, but we know Jesus is who we all need, regardless of our financial standing.

While the relationship with Jesus is most important, we have a responsibility to be in relationship with one another as well. It’s good for churches to provide opportunities for their constituents to minister to the poor. It’s better for churches to challenge their constituents to be in relationship with the poor — those sitting next to them in church, at PTA meetings and at work.

Many of us would prefer to minister to poor strangers than develop relationships with the poor who are right next to us. We should feel more responsible for those in our path than those we will only encounter at an outreach.

How Leaders Can Respond

1. Develop leaders. To truly meet the diverse needs of the people in your church, you must go beyond volunteer recruitment to leadership development. Volunteers fill a need, but leaders help create culture. To truly become a diverse church in every way, you will need more leaders. Volunteers carry out tasks. Leaders know why they’re doing what they’re doing and influence others to join them.

It’s crucial to share the research you’ve gathered with your leaders so they understand what you’ve learned about your community and why you may begin ministering in new ways. Research will help create new language, and new language will paint a picture that will both motivate and equip leaders to respond to the needs in your community.

2. Go beyond outreach to integration. What happens when the people we minister to outside the walls of our church become the people inside the walls of our church? Many churches understand the need for evangelism strategies and outreach events, but most are not equipped to handle the corresponding success of those approaches. Becoming a diverse congregation and integrating people from all walks of life into the life of the church will require a healthy amount of focus and leadership.

If you’re reaching out to people who are from different backgrounds and socioeconomic classes than the people currently in your church, what is the plan for them to interface with one another? Have you prepared your church to welcome people who are from different neighborhoods? Are your people prepared to invite newcomers into their small groups, and even their homes? They must desire not just to minister to them, but also to be in relationship with them.

3. Evaluate family ministry. Payne notes that many areas of our society operate under the hidden rules of the middle class. The classroom is typically one of these places, and as many children’s ministries are structured as classroom environments, our children’s ministries may be operating under these hidden rules as well. This could make for an environment that is not friendly or even fair to all socioeconomic classes. To better understand these hidden rules, we recommend reading A Framework for Understanding Poverty.

Conclusion

Biblical justice demands that the gospel bring holistic impact to people and places. Therefore, churches cannot ignore the devastating effects within the culture of poverty and its crippling generational implications.

As pastors, volunteers, educators, and members of our churches and communities, we need to be aware of socioeconomic diversity and become intentional about understanding and bridging the gap so that the church can effectively reflect the hope of the gospel in our communities and in the soul of each person we encounter.

This article originally appeared in the April/May 2017 edition of Influence magazine.

Influence Magazine & The Healthy Church Network

© 2025 Assemblies of God