Mercy at the Off-Ramp

Review of ‘Low Anthropology’ by David Zahl

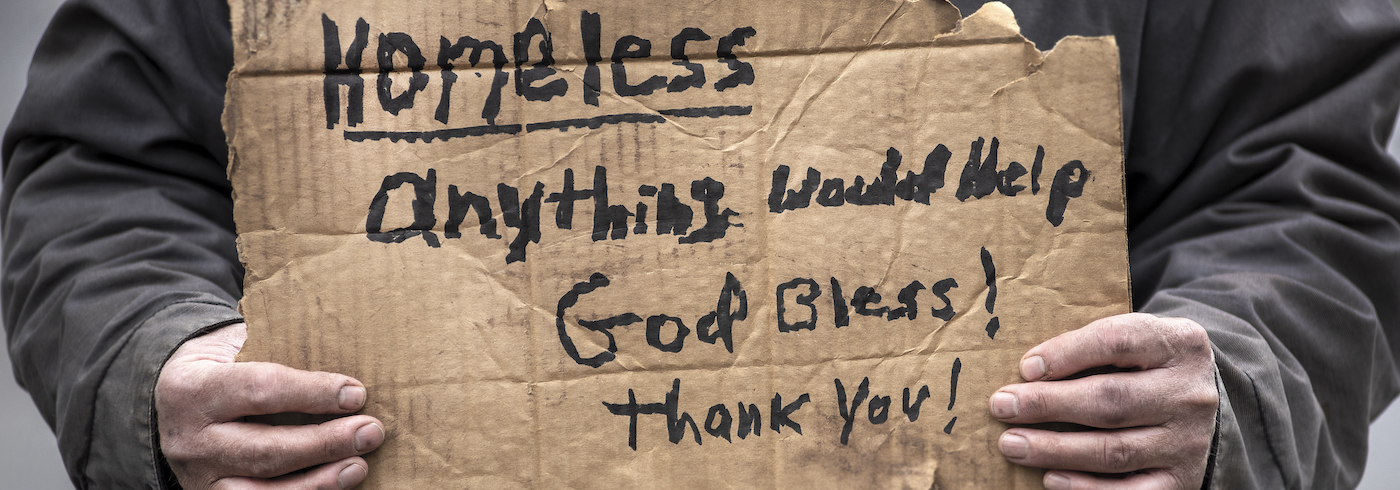

When I drive home from work, I often see a guy at the bottom of the off-ramp holding a cardboard help-me sign. I rarely carry cash, so I have none to give him. Still, I do my best to avoid his gaze.

I can’t avoid the debate taking place in my head, however. On the one hand, this guy probably made a lot of bad choices, and giving him cash would simply allow him to continue his losing streak. Good thing I don’t have any!

On the other hand, I know what it’s like to be in debt. Maybe he had a run of back luck and simply needs someone to notice and help. I should’ve lifted a Lincoln from my wife’s wallet this morning!

David Zahl would say that my internal debate is about anthropology, that is, “our operative theory of human nature.” Specifically, it’s a debate between high and low anthropologies. High anthropologies offer “sunnier estimations of what women and men are like,” he writes, while low anthropologies offer “more sober estimations.”

A high anthropology sees help-me guy as a moral agent capable of making choices. He is on life’s off-ramp because of bad choices. Good choices will put him on life’s on-ramp once again. Whether off or on, help-me guy is in control, which is why I hesitate to give him money.

According to Zahl, a low anthropology sees “the human spirit as something that veers, by default, in a malign direction and, as a result, cannot flourish without assistance or constraint.” In this view, “people [are] finite, blind, and, in many cases, quite weak,” which is why I probably should give help-me guy money.

My thoughts about help-me guy, however conflicting, assume a high anthropology for myself. I’ve made good choices. I have the money to help. Whether I choose to help him or not, I am different than him.

"If you want to see an increase in hope, understanding, and unity amid the engulfing mercilessness of today ... you must begin with a low anthropology.” —David Zahl

A low anthropology challenges that assumption. “Everyone is screwed up, broken, clingy, and scared, even the people who seem to have it more or less together,” writes Anne Lamott, whom Zahl quotes approvingly. “They are much more like you than you would believe. So try not to compare your insides to their outsides.”

When we take a closer look, whether at others or ourselves, we find that we all have three qualities in common. Zahl calls them limitation, doubleness, and self-centeredness.

“Limitation means that we are bound by time and biology and history and all sorts or other factors that shape our behavior,” writes Zahl. Such factors impose constraints on what we can do and know. I may want to ride roller coasters with my kids, for example, but I can’t because of fused vertebrae and hair-trigger motion sickness.

Doubleness has to do with “the competing forces, or voices, that drive our behavior.” Like many Americans, I’m overweight. I know that I need to eat right and exercise. But given the choice, I prefer donuts for breakfast and a comfy recliner where I can read books for hours on end.

Finally, there’s self-centeredness. Our desires, contrary as they are, “veer toward the self, such that what we want comes at a cost to other people,” writes Zahl. I’m never too busy to read a book. (It helps that I’m an editor by trade.) But how often have I been too busy to play with my children?

These qualities are depressing, but Zahl thinks that acknowledging them is the first step in the right direction. “I am convinced that if you want to see an increase in hope, understanding, and unity amid the engulfing mercilessness of today — indeed, if you want to communicate anything approaching grace — you must begin with a low anthropology.”

Why? Because low anthropology begins with humility. “A high anthropology entertains the possibility of mastery and comprehensive understanding,” Zahl writes. “It can therefore be highly judgmental in practice.” Like me judging help-me guy’s choices in life from behind rolled-up windows.

“If you and I are finite beings, then we are incapable of making watertight judgments of others,” writes Zahl. “There is always a piece of evidence that might be missing.” Humility rolls down the windows, asks questions, and offers the possibility of relationship.

Even more, humility leads us to acknowledge our own weaknesses. I may not stand at the bottom of an off-ramp, but I am help-me guy in my own way. At least he has the honesty to hold up a sign.

I encourage you to read David Zahl’s Low Anthropology for yourself. Better yet, read it with others. It is a wise, witty, and well-written book.

Indeed, without being preachy or proof-texty, it’s a deeply Christian book. Our lives are characterized by both creatureliness (limitations) and sin (doubleness, self-centeredness). Because of that, what we most need is grace, both from God and one another.

As Zahl quotes Reynolds Price in the book’s epigraph, “The whole point of learning about the human race presumably is to give it mercy.”

Book Reviewed

David Zahl, Low Anthropology: The Unlikely Key to a Gracious View of Others (and Yourself) (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos, 2022).

Influence Magazine & The Healthy Church Network

© 2026 Assemblies of God