The Memphis Miracle at 30

Remembering a time of racial reconciliation for Pentecostals

Thirty years ago, Black and white Pentecostal leaders came together in Memphis, Tennessee, to help heal racial fractures.

On Oct. 18, 1994, they dissolved the Pentecostal Fellowship of North America (PFNA), a predominantly white organization established in 1948.

The following day, diverse denominational leaders formed a new organization, Pentecostal and Charismatic Churches of North America (PCCNA).

Dubbed the Memphis Miracle, this gathering marked the beginning of a strategy for racial reconciliation among Pentecostals.

Unity and Division

The Azusa Street Revival in Los Angeles (1906–09) set the stage for the Pentecostal movement — including the Assemblies of God, founded in 1914.

At Azusa, African American pastor William J. Seymour promoted a vision of “brotherly love” across racial divides.

Frank Bartleman, a white participant in the revival, exulted that “the ‘color line’ was washed away in the blood” of Christ. However, this interracial vision was quickly eclipsed as Pentecostals organized churches largely along cultural and racial lines.

The PFNA became symbolic of the division between white and Black Pentecostals. Although the organization claimed broad Pentecostal representation, there were no Black denominations within its ranks.

Throughout the latter half of the 20th century, the Assemblies of God and other PFNA members took steps to include Black adherents. However, majority white and majority Black denominations seemed to run on parallel tracks, with little formal interaction at the national level.

Coming Together

After the 1992 Los Angeles riots, Black and white Pentecostal leaders formed relationships and took intentional steps to bridge the racial divide.

Rather than asking Black denominations to join the historically white PFNA, leaders opted to form a new organization that included diverse membership at the outset.

Gilbert E. Patterson of Temple of Deliverance Church of God in Christ and Samuel Middlebrook of Raleigh Assembly of God co-chaired the local planning committee for the 1994 meeting. Although both men had pastored in Memphis for nearly three decades, they had never met prior to the cooperative project.

More than 3,000 people attended the three-day Memphis gathering. On the morning of Oct. 18, leading Pentecostal scholars Cecil M. Robeck Jr. (Assemblies of God), Leonard Lovett (Church of God in Christ), William Turner (United Holy Church), and Vinson Synan (International Pentecostal Holiness Church) delivered presentations about the sad history of racism, separation, and social neglect.

Synan later recalled, “These sometimes-chilling confessions brought a stark sense of past injustice and the absolute need of repentance and reconciliation.”

Evening crowds worshipped and heard rousing preaching by G.E. Patterson, Billy Joe Daugherty (Victory Christian Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma), and Jack Hayford (International Church of the Foursquare Gospel).

A wave of weeping swept over the auditorium. Participants sensed

this was the Holy

Spirit’s seal of

approval over the proceedings.

The meetings came to a climax during the Oct. 18 morning session when Charles E. Blake (Church of God in Christ) tearfully told those gathered, “Brothers and sisters, I commit my love to you. There are problems down the road, but a strong commitment to love will overcome them all.”

Hayford then interpreted a message in tongues. Hayford said that God poured out His Spirit and over time two separate Pentecostal streams developed, but the waters became muddied, “not by your crudity, lucidity, or intentionality, but by the clay of your humanness the river has been made impure.”

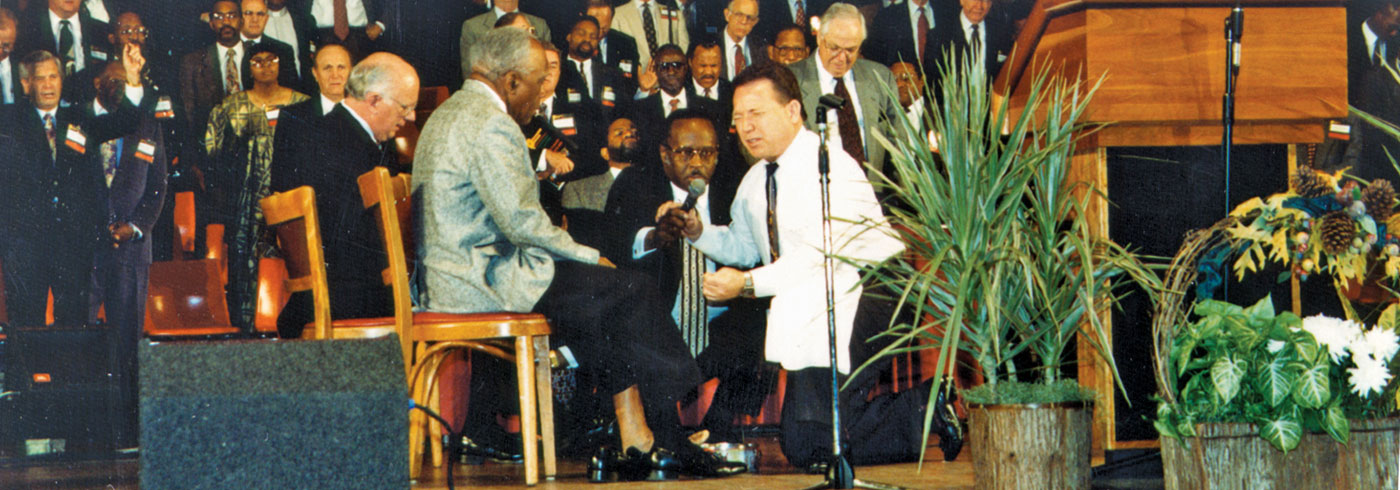

Next, Donald Evans approached the platform. Through tears, the white Assemblies of God pastor explained that he felt God’s leading to seek forgiveness for historical racial discrimination while washing the feet of Church of God in Christ Bishop Ithiel Clemmons.

A wave of weeping swept over the auditorium. Participants sensed this was the Holy Spirit’s seal of approval over the proceedings.

Fruit of Memphis

The 1994 Memphis Miracle gave many Assemblies of God leaders a heightened sense of urgency for racial reconciliation.

In response, the 1995 General Council resolved to encourage the “inclusion of black brothers and sisters throughout every aspect of the Assemblies of God.”

Then-General Superintendent Thomas E. Trask appointed a committee to study the possibility of changing the General Presbytery and Executive Presbytery “so as to more accurately reflect the composition in language and culture of our Fellowship.”

In 1997, the General Council voted to add ethnic fellowship posts to the General Presbytery and expand the Executive Presbytery to include a representative from ethnic fellowships.

With his 2007 election as executive director of U.S. Missions, Zollie Smith became the first Black member of the Executive Leadership Team.

The Fellowship’s Black constituency has increased more than fourfold since 1994. In 2023, 10.9% of AG adherents and 3.3% of ministers were Black.

Lessons

The Memphis Miracle highlights four enduring lessons for church leaders.

1. Big changes often start with small steps. The Memphis Miracle was one event focusing on Black-white relations. Pentecostal leaders recognized the need for bringing together diverse voices.

This became an important catalyst for moving Assemblies of God polity toward better representation of all racial and ethnic groups.

Comprehensive solutions sometimes happen incrementally through conversations and the development of relationships.

2. Everyone has blind spots. Culture shapes perceptions and values more than people sometimes realize. This can lead to the erroneous notion that success within a particular cultural paradigm always equals God’s approval or blessing.

Bringing together people from different backgrounds can help challenge assumptions that may reflect culture more than biblical values.

Hayford explained that it was difficult for leaders to talk about racial reconciliation:

They weren’t conscious sins of antagonistic opposition to other people. They were reflections of our being blinded by our own flesh, our own historic traditions and our culture, rather than being different from the culture. We had become mirrors of the culture, and we did not recognize how unrepresentative of Jesus and His church we were.

3. Progress requires contrition. Pentecostal leaders were remarkably transparent in Memphis, appearing in public before a large audience and acknowledging sin, neglect, and shortcomings in their churches.

Trask told the gathering, “Please fault our past history on race relations where we have erred. But please also help us with a new vision of what the Church can be, and help us with your counsel, your correction, and your prayers of intercession.”

4. History bears remembering. A thoughtful examination of history reveals painful realities, but it can also bring healing.

Trask saw Azusa Street as a compelling metaphor for the Holy Spirit’s work of reconciliation. During his address, Trask called Pentecostals to rediscover neglected truths from their own past:

We desire the multiracial model of Azusa Street not to be an anomaly of modern Pentecostal history, but to become the prototype for what the Holy Spirit wants of the Church in the years ahead. We believe the Holy Spirit intentionally gave us Azusa Street as a beacon and pointer of what we might be. We cannot undo the history of racism that followed the Azusa Street revival. But we can, with the Lord’s help, write a new and better chapter.

This article appears in the Summer 2024 issue of Influence magazine.

Influence Magazine & The Healthy Church Network

© 2025 Assemblies of God