The Idolatry of Bigness

Church size isn’t a problem. Obsession with numbers is.

For decades, American churches did everything possible to generate growth. The focus on more and bigger seemed right. But the cumulative negative consequences are now becoming apparent.

An unhealthy chasm between the haves and have-nots is splintering the Church and threatening its health and effectiveness. Veneration of bigness is crushing the spirits of have-nots, inflating the egos of haves, and creating a frenzied pursuit of numbers.

I got my first whiff of this when I began pastoring a small church during the late 1980s.

At the time, robocalling was the latest marketing tool. A church consultant recommended the technology for generating buzz and drawing crowds.

In theory, 20,000 calls yielded some 2,000 positive responses, attracting 200 attendees on launch day for new church plants. Twenty of those attendees would become full-time church members.

Established churches could expect only half that response, the consultant added. To gain 20 new members, we would need to make 40,000 robocalls. Setting up such a campaign would require hundreds of work hours and cost more than a quarter of our church’s annual budget.

The consultant assured us the numbers were in our favor. If we invested the funds (which he offered to loan us with interest), the 20 newcomers would pay for it with their tithes in less than a year.

Intriguing as this was, I had questions: “What happens if our church goes into debt, but the new members don’t stay or don’t give? How can I recruit enough volunteers to manage 40,000 phone calls? People hate robocalls, so why would we want to do something everyone dislikes?”

Finally, I said, “I’d rather do something of value, like feeding hungry people, helping single moms, or offering classes where unchurched community members can ask hard questions and have healthy, biblically guided conversations. If no one becomes a regular attender, at least we will have shared Christ’s love and pointed people to Him. Isn’t that a better option?”

“No,” the consultant insisted. “Those types of programs get far less numerical return. We’re recommending robocalls.”

We ultimately declined the offer. I later spoke with a local church planter who tried robocalls and saw few lasting results.

Not surprisingly, the robocalling approach to church growth didn’t last long. But the obsession with getting people in the building at all costs remains.

Crowd Chasing

The Great Commission mandate is to make disciples, not attract crowds (Matthew 28:19–20). In fact, even as Jesus drew followers, He preached difficult truths that reduced their ranks (John 6:60–66).

According to the Book of Acts, “large numbers” converted to Christianity in Ephesus (19:26). The church in that city grew so rapidly pagan shrine makers felt threatened and started a riot (verses 23–41).

Nevertheless, an assessment of the Ephesian church in Revelation offered no comment on the congregation’s size. Instead, the resurrected Jesus called on members to repent over forsaking their first love (2:1–7).

Christians at Laodicea felt secure in their wealth. But the Lord critiqued their lukewarm faith and exposed their poverty of spirit (3:14–22).

Meanwhile, Jesus honored the faithful church in Philadelphia, even though they had “little strength” (3:8). And He comforted the persecuted congregation in Smyrna, saying, “I know your afflictions and poverty — yet you are rich!” (2:9).

No honest reading of such passages can lead us to think Christian ministry is all about attracting crowds and amassing resources. Yet wealth and attendance have somehow become the measures of American evangelical church success.

By this metric, growth and strength are synonymous with numerical increase. If a congregation is not seeing an annual uptick in attendance, we assume it is stuck, broken, or dying — regardless of its health.

When numbers take priority over spiritual flourishing, we have a problem. An obsession. And this obsession is causing us to behave in ways that are not only unhelpful, but also idolatrous.

Biblically, idolatry doesn’t start with physical objects, but with futile thoughts, foolish hearts, and claims of wisdom (Romans 1:21–25).

While Old Testament teachings against idolatry tended to focus on the worship of physical things, New Testament writers listed idolatry alongside sins of behavior and the heart (Galatians 5:20; Colossians 3:5; 1 Peter 4:3). An idea can be an idol.

Bigness as Idolatry

Of course, there is nothing inherently wrong with large congregations. Reaching more people with the gospel is a good thing.

Yet today there is an unrelenting demand on churches to get bigger, faster. It is burning out pastors, tempting leaders to compromise their values, and diverting attention from what matters most.

Most church growth conferences over the past 40 years have featured leaders of the biggest congregations. Pastors from smaller settings gather to

learn the secrets of increasing attendance.

Big isn’t the problem; bigness is. Bigness is an attitude, not a number. It is a mindset that prioritizes becoming bigger over being biblical. It contributes to the exaltation of human leaders, which opens the door to other problems.

Pastors who are attracting crowds frequently get a pass on problematic behavior. Christians shrug and say, “The church is growing, so they must be doing something right.”

In his forthcoming book, The Gift of Small, Allan T. Stanton recalls the following exchange:

Once, while touring an area of my state with a denominational regional official, the official pointed out a small church and said, “That church is successful. It’s growing like crazy. The theology is terrible — not at all what we teach. But they’re growing!”

I wish I could say this is surprising. But I’ve heard similar comments too many times. When increase is more important than integrity, that’s idolatry.

Jesus cautioned His followers to count the cost before building towers (Luke 14:28–29), and to focus on the condition of their souls rather than the size of their barns (Luke 12:16–21).

In recent years, we’ve become almost immune to the shock of pastors failing morally. On numerous occasions, I’ve talked with staff members in the aftermath of such situations and heard them say, “That’s just how our pastor was. He was known to be a little handsy (or crude, flirty, or volatile), but no one challenged him on it because the church was growing.”

As undershepherds of God’s flock, we must stop overlooking character flaws in favor of numerical increase. The biblical requirements for church leaders have nothing to do with quantifiable results, and everything to do with character (1 Timothy 3:1–7; Titus 1:6–9).

Providing cover for habitually bad pastoral behavior is a common symptom of the idolatry of bigness.

Wanting more people to come to church is a good motive, of course. But that’s the way it is with idolatry. Even if it starts with noble intentions, it is a problem when it stops pointing to God and starts replacing Him in our hearts, minds and priorities.

While the First Commandment forbade worshipping other gods, the Second prohibited creating an image for worship, including one of the true God (Exodus 20:3–4). That’s because an idol can become a stand-in for God without us even realizing it.

Increased numbers start out as a visible manifestation of God’s invisible blessings. Rising attendance can glorify God — that is, until it becomes our singular focus. That’s when it takes on the status of an idol.

Church Growth History

In the ministry world, numbers define us. They shouldn’t, but they do. The pastor leading a congregation of 3,000 receives more credibility than a pastor of 300 — and considerably more than a pastor of 30. The Church has an unhealthy relationship with bigness.

This is especially true in the American Church. And it’s destroying us. Pastors are leaving ministry over their inability to get the numbers up. Those who remain are dealing with stress and burnout at record levels — regardless of church size.

Bigness is a craving that always demands more. An obsession with numbers may be the least-acknowledged major contributor to pastoral departures, ministerial burnout, congregational division, moral compromise, and a long list of other church dysfunctions.

How did we get here? The answers are not simple, but the cult of bigness has been decades — if not centuries — in the making.

Donald McGavran was an American missionary to India from 1923–54. Near the end of his tenure, he heard about entire villages in India and beyond that were coming to Jesus en masse.

Skeptical of the reports, McGavran visited several Indian villages and discovered that what he had heard was true. So, he decided to study what was happening.

Upon retiring from his missionary position, McGavran traveled to several African nations where similar events were occurring.

McGavran later published his findings in The Bridges of God. It introduced a number of terms and ideas that are part of evangelical vernacular today, including the phrase “church growth.” In fact, this book has been called the Magna Carta of the church growth movement.

In 1965, McGavran started the Church Growth Institute at Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, California. For the first seven years, admissions requirements included foreign missions experience, fluency in a second language, and demonstrated field knowledge of an indigenous context outside the student’s own.

By design, these standards excluded most American pastors. McGavran worried they would use his principles to make U.S. churches bigger rather than helping unreached peoples come to Christ.

In 1972, at age 75, McGavran finally gave in to overwhelming requests and co-taught a class with C. Peter Wagner for American pastors. This is universally considered the spark that started the church growth movement.

What did American pastors do with these lessons? Exactly what McGavran feared. We turned it into a race to outgrow the church next door.

The roots of this movement stretch back even further than McGavran, beginning with America’s great founding principles. The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution enshrines several basic liberties, including freedom of religion.

Most European nations during the 18th century collected taxes for state-sanctioned churches. In this way, everyone tithed, whether they wanted to or not. Pastors received their incomes from the government.

The idol of bigness is relentless. Thankfully, the Lord has given us a way to recognize and resist this idol.

In contrast, the First Amendment gave Americans the right to worship (or not) as they saw fit. And most didn’t. Sociologist and religion professor Rodney Stark conducted an analysis of church and census records and estimated that in 1776, just 17% of colonists were churchgoers.

Preachers who could draw the biggest crowds and raise the most money built the biggest churches. Thus, the model of the entrepreneurial pastor was born.

During the church growth movement, these entrepreneurial pastors applied McGavran’s missional ideas and terminology to their American context.

This explains why most church growth conferences over the past 40 years have featured leaders of the biggest congregations. Pastors from smaller settings gather to learn the secrets of increasing attendance.

There is little interest in gleaning wisdom from faithful, small-church leaders. Pastors want to hear from those who have seemingly arrived — so they, too, can grow their churches bigger, faster.

Deception

Bigness is deceptive. It’s easy to feel justified in everything you’ve done when the numbers are up. Bigness acts as its own merit system.

There are two significant ways bigness deceives.

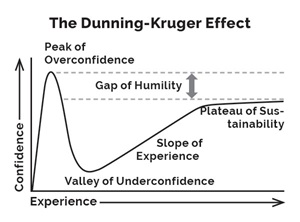

First, bigness contributes to overconfidence. There’s a fascinating phenomenon sociologists call the Dunning-Kruger effect. Studies suggest that during the learning process, there is an inverse relationship between confidence and actual knowledge.

People with just a little knowledge tend to have a higher degree of confidence than they should, while people with considerable knowledge and experience are far less confident about how much they know.

We start our ministry training with little knowledge and little confidence. As we learn, our confidence soars to the top of what I call the peak of overconfidence. This is where many first-year seminary students are.

It’s also why we should be careful not to put people on the platform too early, no matter how gifted they may be. The apostle Paul didn’t need to know about the Dunning-Kruger effect to warn of the conceit that happens when a recent convert rises to a position of leadership too quickly (1 Timothy 3:6).

By the second or third year of pastoring, after we’ve had some hard-earned experience, the reality of ministry complexity kicks in and our confidence plummets to the valley of underconfidence.

This is where many young ministers quit. Ministry is harder than they imagined, so they doubt their calling and walk away. But those who keep going have the chance to enter the slope of experience, in which their experience and confidence rise at the same rate.

Persistence is the key to long-term ministry. Eventually, those who stick with it arrive at the plateau of sustainability. At that point, confidence is high again, but those years of ministry experience keep arrogance in check. This is the all-important gap of humility.

The church growth movement is on this track. A few decades ago, pastors were learning so many new things we became overconfident in our own abilities.

Big-church speakers headlining pastoral leadership conferences reinforced this confidence. Their strategies were working — or so it seemed.

However, not all the facts were in. More recently, many churches have experienced decline, including some larger ones. Among the most-discussed titles on pastors’ shelves are books like The Rise of the Nones, The Great Dechurching, and Autopsy of a Deceased Church.

We’re well into the valley of underconfidence. Some of this is a necessary corrective. No one gets to the slope of experience or the plateau of sustainability without first going through the valley of underconfidence.

In Psalm 23, the Shepherd leads His flock through the darkest valley before they’re ready to receive the table He prepares (verses 4–5). The Lord wants our cups to overflow — not numerically, but with goodness and love (verses 5–6).

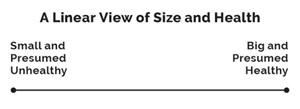

Second, bigness leads to an oversimplification of goals. Many ministers have a shallow, one-dimensional view of what makes a church healthy. They perceive congregational size and health as a continuum, with smaller churches on the unhealthy end and bigger ones on the healthy side. The assumption is that church health increases or decreases in proportion to attendance.

We should know better. Not all small churches are unhealthy, and not all big churches are healthy. Yet church leadership conferences often publish speaker bios that mention church size and the rate at which these congregations are growing.

No wonder we think of big churches as healthy and assume their leaders are always worth following.

Meanwhile, we wring our hands over churches that haven’t grown numerically in a while, concluding they must be stuck, broken and unhealthy. We figure someone needs to fix or close these congregations. Certainly, we don’t expect to learn anything from their leaders — except perhaps what not to do.

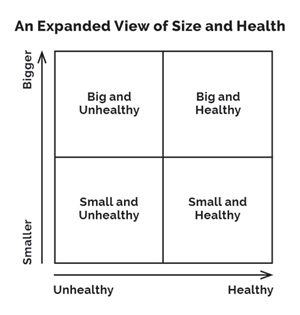

To gain a more accurate picture, we need to expand our understanding of church size and health.

By moving from a simple continuum to a graph with an x-axis and a y-axis, we can treat size and health as separate factors. Yes, there are small, unhealthy churches. And there are big, healthy churches. But there are also small, healthy churches, as well as big, unhealthy churches.

This way of thinking opens some wonderful new opportunities. In this model, we still have a lot to learn from big, healthy churches, but we can also learn from small, healthy churches. This can also protect us from following big, unhealthy churches. Wisdom should always flow from the healthy to the less so, regardless of differences in size or wealth.

Rejecting Idols

The idol of bigness is relentless. It produces tangible results. It gets our adrenaline pumping. It mimics legitimate moves of God. And it demands to be worshipped.

Thankfully, the Lord has given us a way to recognize and resist this idol. We can assess church health non-numerically by reminding ourselves of two foundational, biblical truths.

1. Discipleship fixes everything. Jesus’ ministry instructions are not complicated: “Go and make disciples” (Matthew 28:19).

We call this the Great Commission. It appears in various forms in all four Gospels and Acts (Matthew 28:18–20; Mark 16:15; Luke 24:47–48; John 20:21; Acts 1:8).

Despite my hesitance in most cases to offer one-size-fits-all solutions to complex problems, I know I am standing on firm biblical ground in pointing to discipleship.

There is no church problem Spirit-empowered discipleship can’t fix. Lack of volunteers? Discipleship.

Bad theology? Immaturity? Immorality? Disunity? Discipleship fixes all of it.

So, why don’t church leaders devote more time and energy to discipleship? Unfortunately, the idolatry of bigness gets in the way.

My problem with the idol of bigness isn’t that it’s too big.

Rather, it’s too small.

The only “problem” discipleship may not fix is a church’s size. That’s because size is not actually a problem.

Further, there are times when discipleship requires more commitment than some people are willing to bear, prompting them to leave.

Even Jesus experienced this during His ministry. As Jesus was talking about His body and blood, some said, “This is a hard teaching. Who can accept it?’’ (John 6:60). Then, “many of his disciples turned back and no longer followed him” (verse 66).

If Jesus lost people, why wouldn’t His Church?

Nevertheless, the mandate to make disciples is clear. We must put more of our time and energy into discipleship than gathering a crowd.

2. Integrity is the new competence. For two generations, the Church has taught pastoral competence. Conference after conference has promoted the latest methods, ideas, innovations and technologies.

Unfortunately, while emphasizing technical competence, we’ve often taken integrity for granted. The Church can no longer ignore this issue.

Ministers are adept at creating and using new techniques, but moral failures have eroded public trust — hurting and alienating far too many people in the process.

A church can become big without compromising integrity. I know a lot of deeply principled big-church pastors. But when bigness is the goal, acting with integrity sometimes feels like a roadblock.

Bigness has a pull. It exerts a gravitational force that threatens to consume and control everyone and everything. The lure of bigness brings temptation to compromise discipleship and integrity. Pastors must resist.

The Church cannot manage its way out of a crisis of integrity. Christians aren’t leaving church or deconstructing their faith because worship services lack technical excellence. Yet many are walking away because they see too much distance between what pastors say and do.

For the past several decades, I’ve frequently heard church leadership speakers reiterate the ideas of entrepreneurs, CEOs, and politicians, but I’ve seldom heard them crying from the overflow of their time in prayer and the Word. The idol of bigness may help some of us gain a crowd, but it’s causing all of us to lose our souls.

People are looking for pastors who are sincere shepherds rather than slick entrepreneurs. They need spiritual leaders who will spend time in the gloriously inefficient tasks of prayer, study, visiting the sick, and discipling the next generation of believers instead of leveraging every waking moment for numerical results.

We keep hearing that churches and companies become great by writing strong mission statements and setting huge goals, and then pursuing them. As the theory goes, an objective that doesn’t scare you is too small, and a plan without a huge numerical component is doomed to failure.

I like to make plans and set goals, but I don’t need to cast a big vision. Jesus gave us the biggest vision of all — to live and share the gospel that is redeeming creation back to the Creator (Romans 8:19–23).

My problem with the idol of bigness isn’t that it’s too big. Rather, it’s too small. This vision may be crowd-sized, but it’s not God-sized.

The era of celebrity pastors must come to an end. We cannot chase a platform and take up our cross at the same time. Instead of setting bigger plans, we need to set a moral compass.

This article appears in the Summer 2024 issue of Influence magazine.

Influence Magazine & The Healthy Church Network

© 2025 Assemblies of God